Knowledge is power: The importance of measuring early development.

(This article was first published at Medium)

Fact: All of us were babies at one point. And unless you were born after 2010, your parents had no idea how many times you moved during the night or what your heart rate was when you were lying down in your crib.

And you are (hopefully) healthy and turned out just fine.

It’s 2023 and there are countless fancy technologies swarming upon today’s nurseries. Having experienced sleep deprivation in my own early months of motherhood, I understand why parents find it comforting to know that every heartbeat and breath of their baby is being watched. Learning about your baby’s sleep routine, knowing that they are safe in the crib at night, and waking up to cute snippets of video are wonderful experienced enabled by modern technology.

However, these features are only scratching at the surface of the potential for connected devices to deliver deep insight on the development of our children. Imagine telling parents that their baby’s movement in the crib is a correlated precursor to standing and walking on their own; this could trigger proactive childproofing of the house before and incident arises. What if monitoring of a child’s responses to audio stimulus could inform parents of hearing issue? How valuable would it be to identify developmental disorders years in advance simply by tracking your child’s basic verbal and motor skills?

While deriving insight from data points across all aspects of a child’s life may seem an impossible task, to ignore the value hidden in these observations is to be negligent to an opportunity for better lives for our children. However, uncovering this value presents countless challenges: privacy concerns, accurate findings, limited clinical validity, and of course, driving parents crazy with more anxiety-inducing information that they’re expected to process.

So why are we going through this uphill battle and are urging you to join us? The answer is two fold:

1/ Data holds the power to making better health decisions for your child

2/ Ignoring infant data is to ignore an opportunity to help

1/ If you can’t measure your baby’s health and development, you can’t improve it.

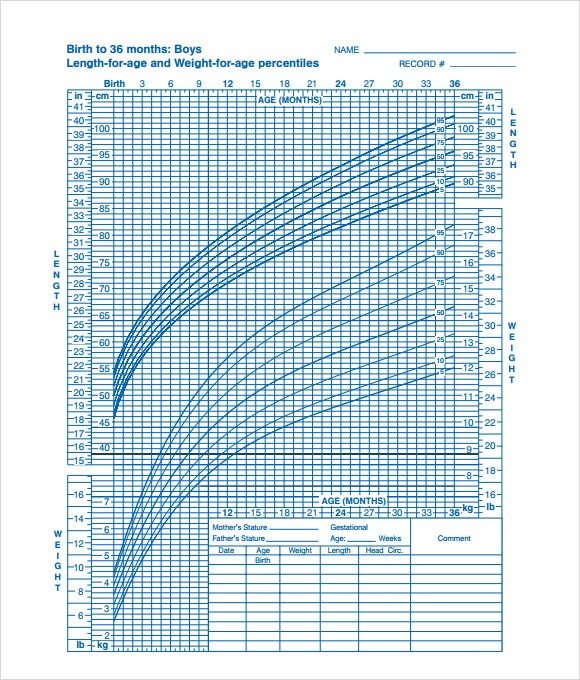

Each newborn child is unique. As they grow, their physical and developmental differences become more evident. Since 1977, doctors have used growth charts to measure how a baby’s height, weight, and head size compare with averages of their age. Ask any new parent about their baby’s weight and they’ll know both the weight of their child and the percentile. Knowing how a baby’s weight compares to their age norms helps parents and doctors understand if a baby is growing as expected or if dietary changes or other interventions are needed.

Now ask the same parent about their baby’s development and the answer is never as clear as it is for height or weight.

We know that 80% of the brain is developed in the first 3 years of life. Few people would argue that brain development is less important than height and weight and yet we have comparatively crude tools and tests for tracking brain health. Yet why is it that we don’t have more sophisticated tools for measuring activities that are correlated to brain health? This includes fine and gross motor, speech, language, social skills, and more.

You may believe that we simply lack a good metric for measuring an infant development similar to how we measure their weight. This may be true for some aspects of development, however, not for all.

Let’s take speech and language as an example. A trained paediatric speech pathologist who has been studying children will tell you there are concrete milestones that babies are expected to hit in the first 12 months of life. They produce vowel sounds around 4 weeks and start to combine vowel sounds with consonants to produce proto-words and various speech utterances, each with a specific timeline.

The CDC recommends that parents should speak to their doctors if a child doesn’t produce repeated syllables of consonant and vowel sounds (i.e. Mama) by 9 months. We know from years of clinical research that babies who don’t hit this milestone are at higher risk of developmental disorders. Conversational turn-taking is another key metric. A longitudinal study done by Lena Foundation found that babies with at least 40 conversational turns per hour between 18–24months scored higher in Middle School Verbal IQ.

These are HUGE findings, and yet how closely are we tracking them?

Imagine if a parent could seamlessly monitor their child’s conversational turns during the day. Paediatricians could have ready-access to this data and could help the parents promote speech development. Imagine the impact this would have on early literacy, childhood mental health, and the long-term benefits on society.

We have the technology to do this today. The issue is not whether we’re able to do it, but rather whether we’re willing to do it!

2/ Ignoring infant data is to ignore an opportunity to help

The first few months being a parent are filled with a strange combination of joy and anxiety. Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) is in the back of every parent’s mind. However, while events like SUIDS happen in 1 in 1100 children, conditions like epilepsy (1 in 200), autism (1 in 36), speech disorders (2 in 10), and many others are far more prevalent than most people think. Helping with these conditions relies on identifying early warning signs and getting a child the right interventions as soon as possible.

If you think we’re engaged in fear-mongering to convince parents to buy more stuff, then I ask you to please stop right here and continue on with your day. However if you believe that data can make you a more empowered parent, then stay right with me. I want you to listen to the stories of parents whose concerns were not taken seriously when they first realized something wasn’t right about their baby’s development.

“First I saw head banging or swaying. I noticed sensory behavior like toe walking and a lot of arm flapping. My daughter was diagnosed this year as moderate to severe ASD. She still is not speaking either. I would like to add that she is our second child with Autism and I knew what to look for … the Dr ignored my concerns for almost a year before agreeing that my daughter not speaking at all was concerning now.” — Claire

“We still don’t have a diagnosis however it was my mom that first noticed, he was still not able to sit up at 8–9 months. My mom’s concerns triggered appointments to follow up with paediatric developmental specialists at the hospital” — Alana

“I didn’t realize something was wrong with my sons speech until someone pointed it out to me. Not every parent figures it out.” — Christina

These are a few examples from countless parents that we’ve spoken to in our journey. Some noticed early red flags but didn’t know how to get a practitioner’s attention. Others didn’t even know that their child’s behavior was atypical. Regardless, with any parent we’ve spoken to with these stories one thing is consistent: they would do anything to go back in time and help their child earlier.

I write this article as a cry for help, however, not for me. I plead with you for the kindergartner whom teachers are only beginning to understand why they can’t pay attention. I implore you to pay attention to the preschooler who’s been called “just shy” enough to distract from the real issue at hand. I beg of you to listen to the deafening silence of the child who’s warning signs — clearly visible with objective data — fall on deaf ears. I ask of you to do better by your child, for you’re the only one who will.

This article was written by Maryam Nabavi and Shane Saunderson, friends, technologists and Babblers at Babbly.co.

References:

https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts

https://www.firstthingsfirst.org/

https://www.cdc.gov/sids/data.htm

https://epilepsysociety.org.uk/