How does Babbly assess my child’s speech?

Written by Iva Brunec, Research Scientist at Babbly

Parents often tell us how helpful it is to have clarity on their children’s speech and language skills. When they upload a video or audio recording and have their little one’s babbling analyzed, it can offer valuable insight. And when you have a clear idea of what kind of skills your child has today, you have even more information to help inform your parental intuition.

At Babbly, we use machine learning to help you understand your child’s speech and language development. Our technology detects and classifies vocalizations when you upload a video or audio recording in the app. Our artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm is designed to analyze audio clips, detect babbling patterns and compare them to language development norms established with the help of Speech-Language Pathologists. With our science-driven approach, we’ve been honing the AI algorithm for some time—and as a scientist, I was especially curious to find out how well the AI-detected vocalizations stack up against the norms. Today, the AI in the Babbly app offers objective insights on the following 5 things:

cooing (strings of vowels: ooo, aaa)

single-syllable babbling (ba, da)

duplicated babbling (baba, dada)

variegated babbling (badupi)

turn-taking (back-and-forth exchanges between the baby and the caregiver)

In this post, we’ll focus on the four babbling types. Generally, they develop in order from cooing to variegated babbling—and gradually overlap as your baby’s language develops. These early language development markers are important to track: the onset of babbling and the complexity of patterns are linked to vocabulary size by age three [1,2], and delays in these milestones can be an early sign of language delay or other conditions [3].

While parents are experts on their child’s development, it can be tricky to tell the difference between early vocalizations without the help of an expert like a Speech-Language Pathologist. This is where Babbly’s AI can be helpful: we trained it to look for patterns in a child’s speech and use them to classify sounds from video and audio clips uploaded in the app.

But accuracy is important—especially for parents who are trying to get clarity on their child’s speech development. To understand how accurately our AI is at detecting infants’ speech milestones, we explored the alignment between the vocalizations detected by Babbly and typical babbling development norms.

Babbling timelines according to speech-language science

When it comes to speech and language milestones, there is a lot of variability between different sources. There is no single source of truth, which can cause confusion for parents. In order to account for the differences between sources, we looked to general patterns: we first charted development norms drawing on 8 sources of developmental milestones [4-11], and added in 13 primary research articles as well for good measure [12-24].

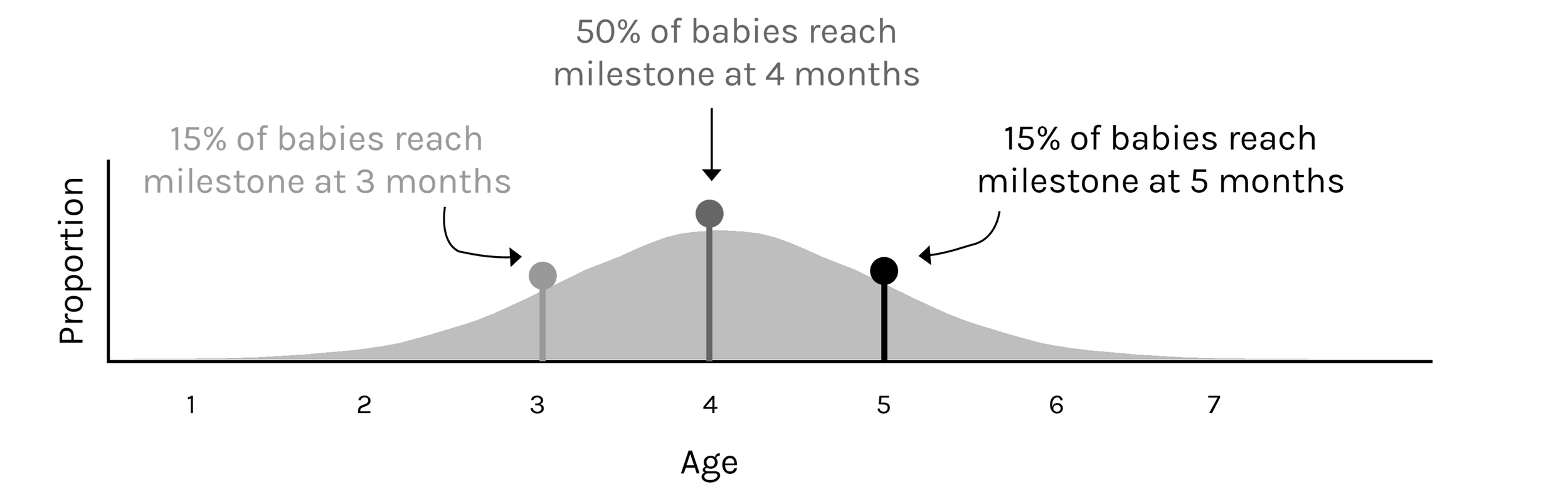

We counted the number of times each babbling type was reported in each source for each month of age. For example, one source might say that a particular type of babbling should happen at two, three and four months, while another source says it should happen at three, four and five months. Then, we put all that information in a bell curve. Think of these curves as a way of visualizing where the different sources overlap, and the peak as the average age that a given skill develops. As we move along the edges of the curve, the percentage of children who develop the skill earlier or later than average becomes smaller and smaller. To help us visualize, we created a bell curve for a hypothetical skill below.

Development of an example skill, where 80% of babies reach a given milestone between 3 and 5 months, with the majority (50%) reaching the skill at 4 months.

Visualizing the different milestones

Plotting the averages of the four different babbling types this way, we see a steady progression from cooing to single syllable babbling, followed by duplicated and variegated babbling. Some sources argue that duplicated babbling happens before variegated babbling [13], while others argue that they develop at the same time [17].

Normative data for different babbling types.

Each curve is like a snapshot of what all the different sources say about each particular skill. And now that we have these “normative bell curves,” we can compare the information against our results from the Babbly AI.

How the normative curves compare data from the Babbly app

So, how well does our AI detect the babbling milestones when compared to the benchmarks above? To answer this question, we took our own data from a one-year period (July 2021-July 2022) and looked at every individual skill detected across all videos or recordings that parents and caregivers uploaded in the app. A total of 3,713 vocalizations were detected during this time period. We created our own bell curves and mapped them against the norms from the sources.

The plots below show the alignment between our own data from the Babbly app (solid lines) against normative data from the plot above (dashed lines).

Babbling types detected in the Babbly app (solid lines) vs. normative data (dashed lines), across age.

These charts match up fairly well—with a bit more variability across age in the variegated babbling category.

When we looked at our AI’s outputs, we found that the data from all four categories of fell within the range set by the language development sources. This means our AI does well at detecting different babbling types as babies progress in their language skills—and it tracks the ages of guidelines pretty closely. These data show that the Babbly app can be a reliable way of tracking a child’s expressive speech milestones before they develop their first words. Right now, we’re looking further into whether these patterns differ for premature vs. full-term babies and babies raised in bilingual vs. monolingual households. Keep an eye out for those results in the future!

Footnotes

Different experts might rely on different guidelines. Here, we plotted the general agreement across milestone guidelines. Not all of the milestone guides listed all 4 babbling types, and none of the research articles focused on all 4 babbling types, but we used these sources to derive the most commonly listed ages at which different babbling stages are expected to develop.

The normative curves represent when a skill should develop. This does not mean that a more advanced type of babbling fully replaces a preceding stage. In the app, we want to show caregivers the most advanced skills as they develop, so as soon as we see evidence of duplicated babbling, we no longer display cooing. It is also possible that early words comprise some part of the ‘variegated’ babbling - with our current AI model, we cannot distinguish between those alternatives.

This analysis does not allow us to say whether some of the detected events are false positives - ‘cooing’ events past one year of age may be false positives, or they may signal atypical development.

References

Camp, B. W., Burgess, D., Morgan, L. J., & Zerbe, G. (1987). A longitudinal study of infant vocalization in the first year. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 12(3), 321-331.

D'Odorico, Laura, et al. "Characteristics of phonological development as a risk factor for language development in Italian-speaking pre-term children: a longitudinal study." Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 25.1 (2011): 53-65.

Oller, D. K., Eilers, R. E., Neal, A. R., & Schwartz, H. K. (1999). Precursors to speech in infancy: The prediction of speech and language disorders. Journal of communication disorders, 32(4), 223-245.

https://sac-oac.ca/sites/default/files/resources/SAC-Milestones-TriFold_EN.pdf

https://www.speech-language-therapy.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=34

Fagan, M. K. (2009). Mean length of utterance before words and grammar: Longitudinal trends and developmental implications of infant vocalizations. Journal of child language, 36(3), 495-527.

Mitchell, P. R., & Kent, R. D. (1990). Phonetic variation in multisyllable babbling. Journal of Child Language, 17(2), 247-265.

Nathani, S., Ertmer, D. J., & Stark, R. E. (2006). Assessing vocal development in infants and toddlers. Clinical linguistics & phonetics, 20(5), 351-369.

Nathani, S., & Stark, R. E. (1996). Can conditioning procedures yield representative infant vocalizations in the laboratory?. First language, 16(48), 365-387.

Rome-Flanders, T., & Cronk, C. (1995). A longitudinal study of infant vocalizations during mother–infant games. Journal of Child Language, 22(2), 259-274.

Smith, B. L., Brown-Sweeney, S., & Stoel-Gammon, C. (1989). A quantitative analysis of reduplicated and variegated babbling. First Language, 9(6), 175-189.

van der Stelt, J. M. & Koopmans-van Beinum, F. J. (1986). The onset of babbling related to gross motor development. In B. Lindblom & R. Zetterstrom (eds), Precursors of early speech, 163–73. New York: Stockton Press.

Elbers, L. (1982). Operating principles in repetitive babbling: a cognitive continuity approach. Cognition 12. 45-63.

Oller, D. K., Eilers, R. E., Neal, A. R., & Cobo-Lewis, A. B. (1998). Late onset canonical babbling: A possible early marker of abnormal development. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 103(3), 249-263.

Kent, R. D. (2021). Developmental functional modules in infant vocalizations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(5), 1581-1604.

Moeller, M. P., Thomas, A. E., Oleson, J., & Ambrose, S. E. (2019). Validation of a parent report tool for monitoring early vocal stages in infants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(7), 2245-2257.

Stark, R. E. (1978). Features of infant sounds: The emergence of cooing. Journal of Child Language, 5(3), 379-390.

Coplan, J., & Gleason, J. R. (1990). Quantifying language development from birth to 3 years using the Early Language Milestone Scale. Pediatrics, 86(6), 963-971.